- ≡ Hypnum stramineum Brid., Muscol. Recent. 2(2), 172 (1801)

- ≡ Calliergon stramineum (Brid.) Kindb., Canad. Rec. Sci. 6: 72 (1894)

Elements in the following description are taken from Hedenäs (2003).

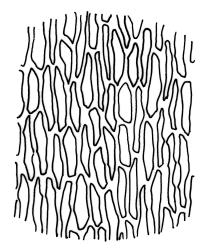

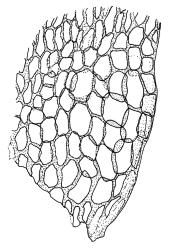

Plants rather slender, yellow- to brown- or bright-green, forming extensive wefts or mats. Stems mostly 25–55 mm, not or very sparsely branched, creeping or self-supporting and ascendant, often among other mosses, in cross-section with hyaloderm lacking and central strand present. Stem leaves imbricate or loosely spreading, broadly ovate, rounded or obtuse at apex, not cucullate, 0.8–1.5(–1.8) × c. 0.5–0.6 mm, distinctly striolate when dry (usually less so when moist), auriculate and weakly or distinctly decurrent at base, occasionally with abaxial rhizoids arising from enlarged cells near apex; mid and upper laminal cells linear-rhomboidal, mostly 21–42 × c. 6 µm, smooth, weakly porose, usually with a few rhizoid initials which are broader and less chlorophyllose than adjacent cells, those at extreme apex shorter; basal laminal cells ± longer, to c. 50 µm; alar cells abruptly differentiated, inflated, hyaline or orange, unistratose, forming an auriculate and slightly decurrent group which does not extend to the costa base; costa unbranched or rarely forked, ill-defined above, mostly extending c. ½ to ⅔ of the leaf length. Branches very sparse or lacking, their leaves not differentiated. Rhizoids smooth, pale brown. Pseudoparaphyllia foliose fide Hedenäs. Paraphyllia absent.

Reportedly dioicous. Sporophytes not seen in N.Z. material.

Kanda 1977, fig. 49, 15–23 (as Calliergon stramineum); Crum & Anderson 1981, fig. 492 (as Calliergon stramineum).

The pale colouration, rounded and shorter and non-apiculate leaves, shorter (mostly 21–42 µm vs c. 66 µm) upper laminal cells, and the usual presence of rhizoid initial cells near the leaf apex differentiate S. stramineum from W. sarmentosa, with which it often co-occurs. Confusion with any other species seems unlikely.

SI: Nelson (Mt Arthur Tablelands, Owen Range, Denniston Plateau), Canterbury (Lewis Pass, Mt Somers), Westland, Otago.

Bipolar? Some or all populations possibly adventive. Widespread in the northern hemisphere and recorded from high elevation sites in the northern Andes (Hedenäs 2003). Seppelt (pers. comm., 29 May 2002) has identified material from Mt Kosciusko and both Hedenäs (2003) and Smith (2004) recorded it from unspecified Australian localities.

Often at the margins of streams or rivulets or in flushes; occurring in red-tussock grasslands and a variety of acidic wetlands including cushion bogs, pākihi, string bogs and Empodisma-dominated rush lands; best developed at higher elevations. At high-elevation (c. 1700 m) in the Remarkable Range (Otago L.D.), S. stramineum forms nearly-pure mats of several square metres extent at margins of flushes in which Oreobolus pectinatus and Caltha novae-zelandiae are important constituents. At this locality, S. stramineum occurs in marginally drier microhabitats than Warnstorfia sarmentosa, which also covers areas of several square metres. Sometimes associated moss species include Climacium dendroides, Sanionia uncinata, Sphagnum falcatulum, Warnstorfia sarmentosa, and W. fluitans. The number and quality of collections from the schist ranges of Otago (especially the Old Man, Rock and Pillar, and Remarkable Ranges) suggest that this species is most common and best developed there.

The majority of collections are from elevations of 1200–1800 m. However, some collections from either the general vicinity of Denniston (Nelson L.D.) or from Westland are from lower elevations. Well-documented collections (D. Glenny s.n., CHR 438479) from 700 m near Reefton and from c. 200 m at Kāwhaka Forest, near Kūmara, (P. Wardle s.n., CHR 104413), as well as collections by J.K. Bartlett from the vicinity of Ross and Jacksons Bay, document the occurrence of this species at low elevations in Westland L.D.

Although apparently first collected by G.A.M. Scott in the Old Man Range (Otago L.D.) in 1965, S. stramineum was first recorded for N.Z. in a publication by Bartlett (1984) who described its habitat in Nelson L.D. and Westland L.D. as "boggy, very wet paddocks and grassy depressions alongside roads." In my experience, however, such weedy habitats are less representative of the species than the high-elevation wetland occurrences described above. While Bartlett’s suggestion that S. stramineum occurs in "anthropogenic" habitats and is therefore adventive merits consideration, the presence of high-elevation populations which are strongly integrated into wetland vegetation of remote regions contravenes this suggestion.

With regard to its collection history, documented distribution, and occurrence both in undisturbed high-elevation plant communities and modified low-elevation communities on the SI, S. stramineum exhibits similarities to other "bipolar" species such as Climacium dendroides and Aulacomnium palustre. The possibility that at least some N.Z. populations of S. stramineum are adventive in origin cannot be dismissed. An alternative hypothesis would be that late 19th and 20th century vegetation disturbance permitted the range expansion (within N.Z.) of previously relatively rare, indigenous, high-elevation species (such as S. stramineum) into lowland sites. Molecular comparisons of populations on a global scale would probably be the best way to attempt the resolution of this question for S. stramineum and species with similar distributions and collection histories. Such a resolution is beyond the scope of the present Flora.

Leaf length and laminal cells of the majority of N.Z. collections of S. stramineum are shorter than the measurements usually cited for northern hemisphere populations (e.g., Kanda 1977, p. 85). Sporophytes are rare throughout the range of this species and it is not known to fruit in N.Z.